(Ex University Professor in the Queen’s University, Ireland)

It is rather a daring undertaking to attempt to show in the short time at my disposal how much the world in general, and my profession in particular, is indebted to the genius and work of Pasteur. Also, it may seem presumptuous at this time of day to assume that a number of scientific pharmacists are not thoroughly acquainted with Pasteur’s bequests to medical science, and the benefits reaped by humanity at large from his researches and experimental methods, which have influenced and altered the current of medical thought and teaching in the latter part of the past century.

Still, I am sanguine enough to believe that Pasteur’s work, which I followed for thirty years of his life with intense interest, may have sufficient fascination for others to induce them, if I may so express it, to take “a bird’s-eye view” of it, and that they must draw from this as aI proceed some useful and, I trust, not altogether uninstructive lessons.

First, let us consider what type of man Louis Pasteur was: what was his early life, and what were its associations?

No one can rise from that study without being impressed with the wonderful personality, the exceptional temperament, and the strikingly human and lovable characteristics of teh boy and the man. I take many excerpts from his biography by René Valery-Radot, which has been so admirably translated by Mrs. R.L. Devonshire, and to whose work, published by Messrs. Constable, I am greatly indebted.

His Antecedents

Pasteur was of comparatively humble antecedents, his ancestor six generations back (1682) having been a miller of Plenisette, and afterwards of Douay, in France. The marriage register of his sons shows that he and his wife were unable to write. At Lemny, in the Jura plains, this son was also a miller, and, like his father, was in those feudal times a serf to the reigning feudal lord. It was only in 1763 that his great-grandfather, Claude, a tanner by occupation, obtained his freedom from the lord of Lemny. The son, one of ten children, who followed his occupation, moved to Salins. He married twice, died at the age of twenty-seven, and left one son by his first wife, the father of Louis Pasteur.

This orphan child developed into a hero. He saw active service in the early years of the last century, became a sergeant-major in 1814, and received the Cross of the Legion of Honour. Napoleon’s downfall crushed his spirits, but never shook his loyalty to his old leader. He was an experienced soldier, but only twenty-five years of age when, having taken to tanning, like his forefathers, he married a humble girl, a descendant of vinekeepers–Jeanne Elienette Roqui, one of a family so united that “to live like a Roqui” was a proverb. To this industrious and simple-minded pair Louis was born at the village of Dole, near Arbois, on December 27, 1822, and his first home was practically a village tannery. He lived to see that same peaceful Arbois the scene of pillage and murder, and devastated by war. This was in 1870.

The soldier father was of an artistic nature, and, although untaught, left proofs of natural talent. His first original effort was a bold pastel drawing of his wife–“a powerful face illumined by a pair of clear, straightforward eyes”; those of a mother whose thoughts were ever with the son she loved. His father’s friends were an old army doctor and a studious philosopher. Louis Pasteur “watched his parents dy by day working under dire necessity, and ennobling their weary task by considering their child’s eduction almost as essential as their daily bread. And as in all things they took an interest in noble motives and principles, their material life was lightened and illumined by their moral light.”

When Louis was thirty years of age he wrote of his father thus: —

For thirty years I have been his constant care; I owe everything to him. When I was young he kept me from bad company, and instilled into me the habit of working, and the example of the most loyal and best-filled life. He was far above his position, both in mind and character.

This father was informed of his son’s problems by correspondence, and sat up half the night to work them out in order to teach his sisters. While yearning for his son’s advancement, he could yet write to restrain his ambition. “Before being a captain,” he says, “you must become a lieutenant…” “My satisfaction in you, “he writes in another letter, “is deeper than I can express.”

He was never anxious about Louis’ health, and followed all his scientific work with interest, studying hard that he might understand all its intricacies. “Do tell Louis,” he writes to his son’s close friend, Chappuis, “not to work too hard. That is not the way to succeed, but to compromise one’s brain.”

Pasteur’s mother was a modest, intelligent, and kind woman, fuyll of imagination and ready enthusiasm, keenly solicitous about her son’s education, his physical well-being, and his intellectual advancement. Such were Louis Pasteur’s parents.

His Early Friendships

Next to good family associations, the most important influence on the future of boy or girl is found in their early friendships. Can we not at this moment recall the freelings that animated some early friendship and hallowed it into an undying love? Such friendship was that of Charles Chappuis for Louis Pasteur. “Of these two,” writes Valery-Radot, “everything that makes souls merge into each other was there, so that the seam which originally joined them disappears.”

Charles Chappuis, Pasteur’s boyhood’s friend, was a generous, gentle-faced youth, full of enthusiasm for work, and cherishing for Pasteur the deepest affection. He had a greater love for mathematics and philosophy than for chemistry, but he followed his friend’s researches and discoveries with the greatest interest. For fity years that relationship lasted, continuing until the closing scenes of Pasteur’s life in the little tent in the garden of the Pasteur Institute in Paris.

And now there is the third association of childhood that bears fruit all through life; that is, education. Pasteur’s master at Arbois College, Master Romanet, exerted a decisive influence on his career. His constant aim was to educate the hearts and minds of his pupils. Education meant more to him than mere instruction.

He was the first to discover the hidden spark in his young pupil; he strolled with him round the college playground, talked to him of his future, and animated him with a keen desire to enter the famous Ecole Normale in Paris, founded by Napoleon I.

Pasteur’s character in boyhood and early youth may be judged from some extracts from his letter, and from one or two anecdotes of his early life. There was something of the artist in young Louis. This he probably inherited from his father. His coloured chalks were his delight, and often came the boyish struggle with sentiment and feeling when duty called him to other and less pleasing labours. He was known at Arbois as “The Artist,” and here it soon became beyond the power of his master to teach him more. He left behind him a regular portrait gallery. As a boy, he could not trap a bird; the sight of a wounded lark was painful to him, and in after life he could not bear to see a dog trephined.

He was described when a young man as “grave, quiet almost, and shy.” Even then he was of a deeply religious turn of mind. “If by chance you falter on the journey,” he writes to his sisters, “a hand will be there to support you. If that should be wanting, God, who alone would take the hand from you, would accomplish the work.”

Of books he writes: “A good book is a good action constantly renewed; a bad one an incessant and irreparable fault.”

One year at his school he won more prizes than he could carry. From the College of Franche Compté he writes to his father referring to his drawing: –“I prefer first place at College to ten thousand phrases in the course of conversation.” To his sisters he says: –“Dear sisters, let me tell you again, work hard. Love each other as I love you; accustomed to work, it is not possible to do without it…To will is a great thing, dear sisters, for action and work usually follow will, and almost always work is accompanied by success. These three things–Will, Work, Success–fill human existence; Will opening the doors to Success, both brilliant and happy; Work passes these doors, and at at the end of the journey Success comes to crown our efforts.”

That end came to him in 1895 in his seventy-third year. It came, to quote his own words, “in an absolute faith in God and Eternity,” and with a conviction that the good given us in this world will be continued here-after.

“The idea of God,” he said, “is a form of the idea of the Infinite. As long as the mystery of the Infinite weighs on human thought, temples will be erected for the worship of the Infinite, whether God be called ‘Brahma,’ ‘Allah,’ ‘Jehovah,’ or ‘Jesus’; and on the pavement of those temples men will be seen kneeling, prostrate, annihilated, in the thought of the Infinite. At these supreme moments there is something in the depths of our souls which tells us that the world may be more than a mere continuation of phenomena proper to a mechanical equilibrium brought out of the chaos of the elements through the gradual action of the forces of matter.”

His Marriage

And now I come to the last contributory element in Louis Pasteur’s success. On February 10, 1849, at the age of twenty-seven, being then assistant to, and acting for, the Professor of Chemistry at Strasbourg, he wrote the most eventful letter of his life. It was to ask Monseiur Laurent, the eminent Rector of the Academy, for his consent to his daughter’s union with him in marriage. That simple, unaffected, and open letter gives the keynote to another side of his character. In it he says that his father is a tanner in the small town of Arbois, that his sisters keep the house for him and assist him in his books, taking their dead mother’s place. The entire family fortune, he goes on, does not exceed 50,000 francs, and all his share he had made over to his sisters. Therefore he had absolutely no fortune. He minimises all his achievements, though even at this time he had already made a considerable reputation as a chemist.

“Perhaps,” he says, “in ten to fifteen years I may think of marriage; at present, this is a dream.”

This is what he writes to his friend Chappuis after his marriage:–

“Every quality I could wish for in a wife I find in her.” That wife lived to share all his joys, his anxieties, his hopes; the laboratory with her ws to come before everything else, yet she often scolded the young enthusiast for his excessive zeal, and for the five whole days a week spent in that laboratory. All through his eventful life she followed every experiment, and every fresh discovery, of her renowned husband, tending him to the last with loving and solicitous care.

It must suffice for me to enumerate briefly the work that Pasteur did before the arrival of his thirtieth birthday. At seventeen he was Preparation Master at Besancon, receiving board and lodging and three hundred francs a year, and studying all the time. At the age of twenty he had taken his Bachelorship in Letters and Science. Curiously enough, in the latter he was set down as mediocre in chemistry–not the only occasion on which the mere examinational standard has proved fallacious as to future success.

Next we find him in Paris, teaching in the Barbet Boarding-school, and attending Dumas‘ chemical lectures. In his twenty-first year he appears fourth on the list of the Ecole Normale, having obtained some prizes at the Lycée St. Louis. After this we find him making researches into the effects on polarisation of the two forms of tartaric acid–experiments which soon make him the subject of conversation at the Polytechnics. Through these researches he won enthusiastic friends amongst the leading French scientics of the day–Balard, the discoverer of bromine, Biot, the Nestor of chemistry and eminent cyrstallographer; Dumas, the famous chemical lecturer at the Sorbonne, who afterwards acted as sponsor for him at the Academy. It was Biot who exclaimed, in confirming Pasteur’s researches into the polarisation of the tartrates, “My dear boy, I have loved science so much during my life that this touches my very heart.”

Early Successes

To be praised by Biot was considered a great mark of favour. When Regnault thought of making Pasteur a corresponding member of the Institute, Biot wrote to the latter:–“Do not listen to people who without knowing the ground would cause you to desire, or even hastily obtain, a distinction which would be above your real and recognised claim. Be strong enough to disdain yet awhile the accidents which come from men’s caprice.”

Dumas wrote:–“We are not insensible to the glory which your work reflects on French chemistry; the very day I entered the Ministry I asked fo the Cross for you.”

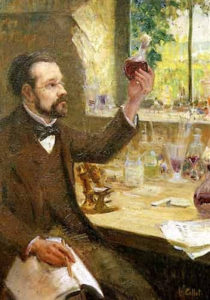

One whole witting of the Academy in 1853, his thirtieth year, was given up to his achievements, and that same year he obtained the Red Cross of the Legion of Hounour, the Grand Cordon of which was afterwards conferred on him. In 1854 he was made Professor and Dean of the Faculty of Science at Lille, the richest centre of industrial activity in the North of France, and shortly afterwards he obtained the Rumford medal of the Royal Society of London. Then came the commencement of the great work which led him on from point to point until it left the whole world indebted to him then and forever, namely, the study of fermentation.

Madame Pasteur ws not far wrong when she remarked, in writing to her father in 1852 of her husband’s experiments in connection with the crystallisation of the tartrates, she said:–“If they succeed they will give us a Newton or a Galileo.” The appreciative wife realised the genius which, in the same year, conceived that the healing of wounds might be compared to the physical phenomenon, which we see when a mutilated crystal is placed in the mother liquor out of which it has grown, and gradually returns to its original shape. “There is a complete analogy,” said Pasteur,” in the wound as in the crystal–the damaged part takes back its original shape.”

At the same time, recognising the symmetry of the universe in the solar system, light and magnetism, he grasped the idea that “all living species are primordially, in their structure and external forms, but functions of cosmic asymmetry; and, further, that the barrier between mineral and artificial products, and those found under the influence of life, was a distinction of fact and not of principle.”

It is absolutely true of all nature that opposing elements produce harmony by neutralisation of effects. Two prisms placed together so that the plane of reflection is the same in both, will reflect light in one direction; if one be now rotated so as to bring it to right angles with the other, no light is reflected–one neutralises the other. So, in living matter, the properties of one form are neutralised by another. Life feeds on life.

The Tartrates Investigation

It had been known that substance precisely similar in the nature and arrangement of their chemical forms and atoms act differently on polarised light. This knowledge, as you know, has give us the saccharimeter. Pasteur utilised this knowledge in distinguishing two substances which had hitherto puzzled the entire scientific world, one being produced in the manufacture of the other–racemic, or partartaric acid (or partartrate of soda and ammonia) a very rare product, and with difficulty obtained; the other, ordinary tartaric acid (as tartrate of soda). The latter gave left-handed polarisation. The former had no action–it was neutral.

Pasteur discovered little faces on half the edges or similar angles of the tartaric crystals. These were at first thought to be absent in the paratartrates. On further examination, however, he found that these hemihedral forms were in the paratartates, but the crystals were asymmetrical and lop-sided, and in some of the faces were on the left, in others on the right. In short, there were two forms of crystals in the racemic acid obtained from the tartaric acid to be thus distinguished.

Pasteur surmised that this same physical difference pervaded all the ultimate molecules of the crystal, and that this molecular distinction explained the differences in their relative actions on light. To test the accuracy of his hypothesis, he determined to isolate and count a number of both kinds of hemihedral crystal. His surmise would prove to be true if the solution of a mixture of an equal number of either kind had no action on the light–in other words, one set would neutralise the other.

“With anxious and beating heart,” says Valery-Radot, “he proceeded to this experiment with the polarising apparatus, and exclaimed ‘I have it!’ His excitement was such that he could not look at the apparatus again. He rushed out of the laboratory, not unlike Archimedes, and, meeting a curator, embraced him as he would have done his friend Chappuis. His surmise was correct. He had discovered two acids out of one–right and left-handed tartaric acid. This led to his famous paper, “Researches on the relations which may exist between crystalline forms, chemical composition, and the direction of rotary power.” The joy of that discovery was shared, as we have seen, by the illustrious Biot.

Next follows a sort of fairy tale of Pasteur’s quest in different countries of Europe in search of this dual-sided substance.

“I shall go to the end of the world,” he exclaimed, “in search of it”; then came his discovery of it in the tartars of Naples, Vienna, Hungary, and Cotia, and lastly, his transformation of tartaric acid in the coveted racemic acid. “Never,” he wrote, “was treasure sought, never adored beauty pursued over hill and vale, with great ardour.” Finally, by a set of most ingenious experiments, he was able to send this telegram on June 1: “Monsieur Biot, College de France, Paris.–I transform tartaric acid into racemic acid. Please inform Messieurs Dumas and Senormant.” “The discovery,” he said, “will have incalculable consequences.”

It is pathetic to read the affection of the old scientist, Biot, for the younger man. Writing to his protégé after this discovery, he–then in his eightieth year–refers to the regard in which he was held by the distinguished Senorman, and adds, “How happy am I to see the affection he bears you, for there will be at least one man who loves and understands you after I am gone.”

Biot taught on until he was past eighty-four. (Men are not all useless and fit for the crematorium at three score and ten.) Radot describes the end of that splendid life as “like a beautiful summer evening in the north before nightfall, when a soft light still envelopes all things.” When handing Pasteur his portrait, the old man said: “Place this near one of your father, and you will unite the pictures of two men who have loved you much in the same way.”

Pasteur Brewing Louis Pasteur – Science, Health, and Brewing

Pasteur Brewing Louis Pasteur – Science, Health, and Brewing